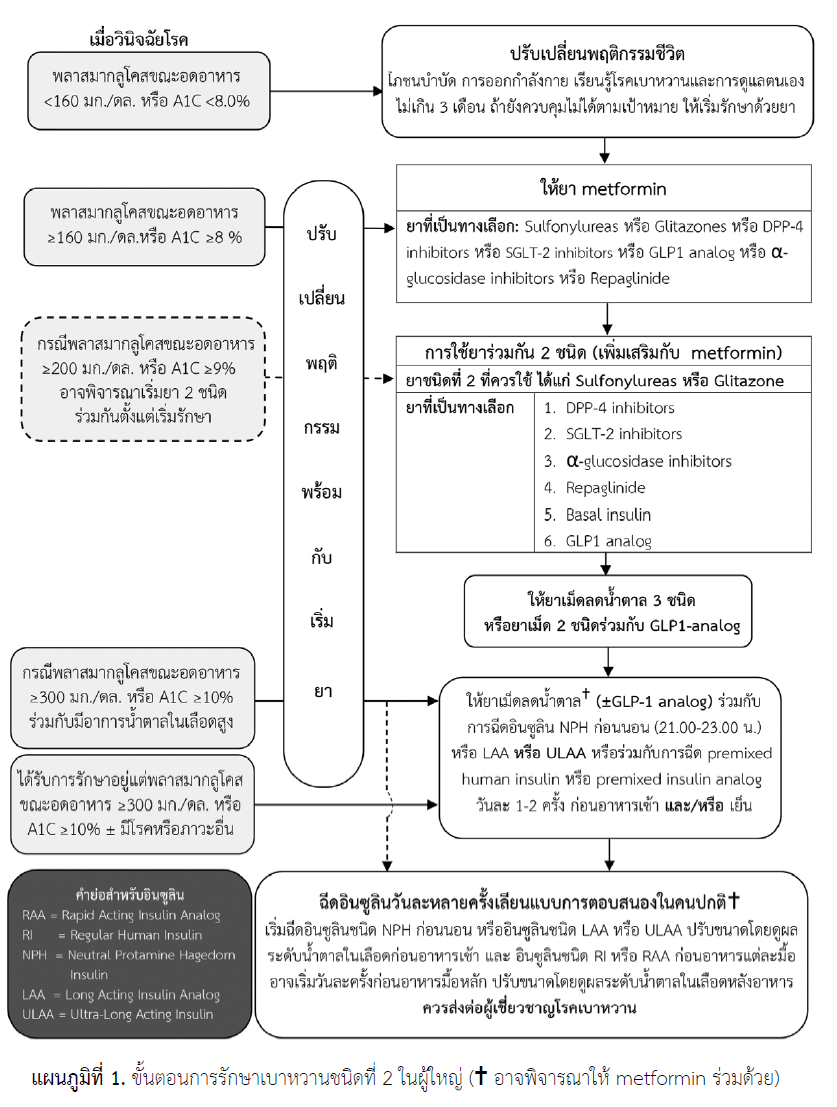

Short Summary of Initial & Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes (Thai Practice)

Initial Regimen: Metformin

Start: Metformin (500 mg) once or twice daily

Titrate: Increase by 500 mg each week (as tolerated)

Maximum Common Dose: ~2,000 mg/day in divided doses

Key Note: Monitor renal function (eGFR). Contraindicated if eGFR <30 mL/min.

Combination Therapy

A. Metformin + Sulfonylureas

Common Thai sulfonylureas:

Glimepiride: Start 1 mg once daily; up to 4–6 mg/day

Gliclazide MR: Start 30 mg once daily; up to 120 mg/day

Key Notes: Adjust dose based on blood glucose control; watch for hypoglycemia and weight gain.

B. Metformin + Glitazones (Thiazolidinediones)

Pioglitazone is the common TZD in Thailand.

Start: 15 mg once daily

Typical Range: 15–30 mg daily (max ~45 mg/day)

Key Notes: Avoid in heart failure (risk of fluid retention/edema); monitor for weight gain.

These regimens form the foundation of dual therapy when Metformin alone is insufficient. All dosing should be individualized, with close monitoring of blood glucose, renal function, and potential side effects.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder marked by persistent hyperglycemia due to either a deficiency in insulin production (Type 1 DM) or insulin resistance coupled with inadequate insulin secretion (Type 2 DM). As Clinicians, we must navigate through these metabolic disturbances by focusing on individualized diagnosis, risk assessment, and multi-modal management strategies that address both glucose control and the prevention of complications.

1. Criteria for Diagnosing Diabetes Mellitus

Blood Glucose Testing remains the gold standard for diagnosing diabetes. The following metrics are employed to confirm a diagnosis:

Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG):

Diagnostic threshold: ≥126 mg/dL (after fasting for at least 8 hours). Elevated FPG reflects impaired hepatic glucose regulation, a key feature of both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

Random Plasma Glucose:

Diagnostic threshold: ≥200 mg/dL, in the presence of classic hyperglycemic symptoms (polyuria, polydipsia, unexplained weight loss). Random glucose testing is particularly useful in the emergency setting or when immediate diagnosis is warranted.

2-hour Plasma Glucose (Oral Glucose Tolerance Test - OGTT):

Diagnostic threshold: ≥200 mg/dL 2 hours post-75g glucose load. OGTT is particularly important in diagnosing gestational diabetes and assessing glucose tolerance in patients with pre-diabetes or metabolic syndrome.

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c):

Diagnostic threshold: ≥6.5%. HbA1c serves as a long-term marker of glycemic control, reflecting average blood glucose levels over the past 2-3 months. A1c is not only diagnostic but also serves as a cornerstone for monitoring treatment efficacy.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations:

Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG): FPG between 100-125 mg/dL.

Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT): 2-hour glucose in OGTT between 140-199 mg/dL.

Pre-diabetes: HbA1c levels between 5.7%-6.4%.

2. Risk Assessment and Screening

Identifying at-risk individuals is essential for timely diagnosis and prevention of diabetes-related complications. Screening should be individualized based on risk factors:

Age ≥35 years and increasing risk with advancing age.

Family history of Type 2 diabetes, especially among first-degree relatives.

Obesity (BMI ≥ 25) or central adiposity (waist circumference >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women).

Hypertension: Blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive therapy.

Dyslipidemia: LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL, HDL <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women, triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL.

History of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).

Physical inactivity: Sedentary lifestyle with minimal physical activity.

Medication-related risk: Chronic use of corticosteroids, atypical antipsychotics (e.g., olanzapine), and immunosuppressants.

3. Pathophysiology of Diabetes Mellitus

Type 1 Diabetes (T1DM):

Autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells: Type 1 DM results from T-cell-mediated autoimmune destruction of beta cells in the islets of Langerhans. The loss of insulin production leads to absolute insulin deficiency, causing hyperglycemia.

Pathogenesis: Strong genetic predisposition (e.g., HLA-DR3/DR4) combined with environmental triggers (e.g., viral infections) precipitates beta-cell destruction.

Key features: Sudden onset of hyperglycemia, ketoacidosis, and reliance on exogenous insulin for survival.

Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM):

Insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction: The core defect in Type 2 diabetes is insulin resistance, particularly in muscle and adipose tissue. This resistance leads to compensatory hyperinsulinemia, but over time, pancreatic beta cells fail to maintain adequate insulin secretion.

Pathogenesis: Obesity, particularly visceral adiposity, plays a central role in driving insulin resistance. Inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), free fatty acids, and ectopic fat deposition in muscle and liver exacerbate the metabolic dysfunction.

Glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity: Chronic hyperglycemia and elevated free fatty acids further impair insulin secretion and exacerbate beta-cell exhaustion.

4. Management of Diabetes Mellitus

A. Lifestyle Modifications (First-Line Treatment)

Dietary Intervention

Carbohydrate Counting & Glycemic Index

Particularly important for patients using intensive insulin regimens (e.g., Type 1 DM) to match insulin dosing with carbohydrate intake.

Mediterranean or DASH Diet

Emphasize whole grains, lean proteins (fish, poultry), fruits, vegetables, and healthy fats (e.g., olive oil, nuts).

Helps improve cardiovascular risk factors.

Caloric Restriction

In overweight/obese patients, reduce calories by 500–1000 kcal/day to foster weight loss and improve insulin sensitivity.

Physical Activity

Aerobic Exercise:

Aim for ≥150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity (walking, cycling, swimming).

Resistance Training:

Perform ≥2 sessions per week to build muscle mass, improving glucose uptake and metabolic health.

Weight Management

Bariatric Surgery may be considered for patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m² and poorly controlled T2DM despite optimal medical therapy, especially with cardiovascular comorbidities. cardiovascular comorbidities.

B. Pharmacological Treatment

Type 2 Diabetes:

First-Line Therapy: Metformin

Mechanism: Decreases hepatic gluconeogenesis; improves peripheral insulin sensitivity.

Initial Ordering Example:

Metformin (500 mg) tab, 1 tab PO once or twice daily

Titrate weekly or biweekly to minimize GI side effects.

Common target dose: ~1,500–2,000 mg/day in divided doses.

Key Cautions:

Contraindicated if eGFR <30 mL/min (and use with caution if eGFR 30–45).

Monitor for vitamin B12 deficiency with long-term use.

If Target HbA1c Is Not Achieved on Metformin Alone

Consider adding one of the following—choose based on patient profile (risk of hypoglycemia, need for weight reduction, presence of ASCVD/CKD/HF, cost, etc.):

Sulfonylureas (e.g., Glimepiride)

Mechanism: Stimulate insulin release from pancreatic beta cells.

Example Order:

Glimepiride (1 mg) tab, 1 tab PO once daily with breakfast.

Titrate up to ~4–6 mg/day if needed.

Watch for: Hypoglycemia, weight gain, cautious use in older adults.

DPP-4 Inhibitors (e.g., Sitagliptin)

Mechanism: Prolongs incretin hormone action, increasing insulin release in a glucose-dependent manner.

Example Order:

Sitagliptin (100 mg) tab, 1 tab PO once daily.

Key Point: Renal dose adjustment if eGFR <50 mL/min.

SGLT-2 Inhibitors (e.g., Empagliflozin)

Mechanism: Inhibits renal glucose reabsorption, increasing urinary glucose excretion.

Example Order:

Empagliflozin (10 mg) tab, 1 tab PO once daily.

Titrate to 25 mg/day if needed.

Benefits: CV and renal protective effects in patients with established CVD/CKD.

Cautions: Risk of genitourinary infections, volume depletion, reduced efficacy if advanced CKD.

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (e.g., Liraglutide)

Mechanism: Enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion, slows gastric emptying, promotes satiety → weight loss.

Example Order:

Liraglutide (0.6 mg) subcut daily for 1 week, then increase to 1.2 mg daily (max 1.8 mg).

Benefits: CV protection, weight loss.

Adverse Effects: Gastrointestinal side effects (nausea); avoid if history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or pancreatitis.

Insulin Therapy

When to Initiate:

If HbA1c remains elevated (>9–10% or so) despite dual/triple oral therapy.

If fasting BG >300 mg/dL or symptomatic hyperglycemia.

Starting Order Example (Basal Insulin):

Insulin Glargine (Lantus) 10 units SC at bedtime, adjust by 2–4 units every 3–5 days according to fasting BG.

Adding Prandial Insulin (e.g., Lispro) if postprandial glucose remains high:

Insulin Lispro (Humalog) 4 units SC before main meals. Titrate as needed.

Type 1 Diabetes

Requires Intensive Insulin (basal + bolus) from diagnosis:

Long-Acting (Basal) Insulin: e.g., Insulin Glargine 10 units SC nightly, titrate to fasting BG.

Rapid-Acting (Prandial) Insulin: e.g., Insulin Aspart 4 units SC before meals, adjusted per carbohydrate counting.

Insulin Pumps / CSII: May be used if multiple daily injections (MDI) do not achieve stable control or to reduce severe hypoglycemia.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM): Aids in minimizing hypo- and hyperglycemia episodes.

5. Advanced Glycemic Monitoring and Targets

HbA1c:

General target <7% for most adults.

Tighter <6.5% in younger/healthier patients if no significant hypoglycemia risk.

<8% or higher in older patients with comorbidities, cognitive/frailty issues.

Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG):

For insulin-dependent or complex regimens, test 3–4 times/day (before meals, bedtime).

CGM:

Consider in patients with frequent hypoglycemia, high variability, or on CSII for better control.

6. Preventing and Managing Complications

Macrovascular Complications

Cardiovascular Risk Reduction:

Manage BP: Target generally <140/90 mmHg, or <130/80 in certain high-risk patients.

Statin Therapy for LDL <70 mg/dL if ASCVD or high risk.

Consider aspirin (75–162 mg/day) for primary prevention in high-risk patients (ASCVD risk ≥10%).

Microvascular Complications

Diabetic Retinopathy: Annual dilated eye exams; timely laser or anti-VEGF therapy if proliferative changes.

Diabetic Nephropathy:

Annual check of urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and serum creatinine.

ACEI/ARB if albuminuria present.

Diabetic Neuropathy:

Regular foot exams; promptly treat ulcers or infections.

Painful neuropathy may be managed with pregabalin, duloxetine, or gabapentin.

7. Diabetes in Older Adults

7.1 Types & Presentation

Often Asymptomatic in early stages; watch for non-specific fatigue, recurrent infections, unexplained weight loss.

Screen for Geriatric Syndromes (polypharmacy, cognitive impairment, depression, falls, urinary incontinence) that can affect self-management.

7.2 Diagnosis & Treatment Goals

FPG ≥126 mg/dL or HbA1c ≥6.5% typically defines diabetes, but individualized interpretation is needed for older adults.

Glycemic Targets:

Relatively healthy older adult: A1C ~7.0–7.5%.

Moderate complexity: <8%.

High complexity or significant comorbidities: avoid hypoglycemia, A1C goal might be more relaxed (≥8%).

7.3 Pharmacological Therapy in Older Adults

Simplify regimens to minimize hypoglycemia risk.

Prefer agents with lower hypoglycemia risk (e.g., DPP-4 inhibitors, SGLT-2 inhibitors if eGFR permits).

De-intensify therapy if benefits no longer outweigh risks (e.g., advanced frailty, limited life expectancy).

Example:

Metformin (500 mg) tab, 1 tab PO BID if eGFR >45.

If needing a second agent, consider Sitagliptin (100 mg) tab, 1 tab PO once daily or Empagliflozin (10 mg) tab, 1 tab PO once daily (monitor eGFR, risk of volume depletion).

8. Initial Medication Ordering Examples

Newly Diagnosed T2DM with no major comorbidity:

Metformin (500 mg) tab, 1 tab PO BID, increase weekly to 1,500–2,000 mg/day if tolerated.

T2DM with ASCVD (e.g., coronary artery disease):

Metformin (500 mg) tab, 1 tab PO BID plus Empagliflozin (10 mg) tab, 1 tab PO OD for CV benefit.

Older Adult with mild CKD (eGFR ~45 mL/min):

Metformin (500 mg) tab, 1 tab PO BID, monitor renal function; may not exceed ~1,000–1,500 mg/day.

If inadequate control, add Sitagliptin (50 mg) tab, 1 tab PO once daily (dose reduction from 100 mg to 50 mg if eGFR <50).

Insulin Initiation (T2DM with high fasting BG ~280–300 mg/dL):

Insulin Glargine 10 units SC at bedtime, adjust +2 units every 3 days until FBG ~100–130 mg/dL.

9. Follow-Up & Evaluation

Frequency: Tailor to severity—often every 1–4 weeks initially for titration, then every 1–3 months once stable.

Monitor:

HbA1c (≥2 times/year if stable; up to quarterly if uncontrolled or therapy changes).

SMBG or CGM data if on complex regimens or insulin.

Blood pressure, lipids, complications (eyes, kidneys, feet).

10. Summary

Lifestyle modifications form the backbone of DM management, which includes diet, exercise, and weight control.

Metformin is first-line for Type 2 DM unless contraindicated (e.g., eGFR <30).

Add-on Agents (Sulfonylureas, DPP-4 inhibitors, SGLT-2 inhibitors, GLP-1 RAs) based on patient factors.

Insulin is introduced when oral therapies cannot meet glycemic targets or if hyperglycemia is severe.

Older Adults require individualized goals; aim to reduce hypoglycemia and simplify regimens.

Complications: Tight control of blood glucose, BP, and lipids is crucial; regular screening for micro- and macrovascular damage.

By following this Thai guideline–aligned recommendations, including proper dosing (e.g., “Metformin (500 mg) tab, 1 tab PO BID”), clinicians can effectively and safely manage diabetes, ensuring both optimal glycemic control and the best possible quality of life for their patients—especially among older adults who may have complex healthcare needs.

Comments